WW II Memoirs – NWFP, Burma – 7th Indian Division

World War II memoirs of my grandfather, P.S. Gill, in NWFP and Burma, comprising 4 essays:

- 7th Indian Division – Some Memories – NWFP-1942

- 7th Indian Division – Some Memories – Jungle Warfare

- 7th Indian Division – Some Memories – Arakan Box

- 7th Indian Division – Some Memories – Arakan – II

The following text is my grandfather’s unchanged. Questions? Email me at karan at karangill dot com. People ask me for more resources on the WWII Indian army. The following are what I know:

- “The Signalman” magazine

- Rana Chhina : Historian

- United Service Institution of India : Finds historical service records

- Burma Star Association

7th Indian Infantry Division – Some Memories – NWFP-1942

On completion of my training (January 1942) at the Cadet College Bangalore, I was assigned to the Corps of Indian Signals, just because, I was informed, my Entrance Form revealed I had studied Physics in college. This meant, five months of additional (Signals) training, at the Signal Training Centre (British) -STC(B)- Mhow, (present day MCTE-Military College of Telecommunication Engineering) and, 5 months seniority loss vis-à-vis the Infantiers. Mhow training turned out to be very elementary really – quite a bit of Visual Signaling (Flag, Lamp, Heliograph –each can send morse code dots & dashes to convey short messages over, say few hundred yards for Flag & Signaling Lamp and, & over a few miles (sometimes 17 miles) for the Holio which on a clear day employs sun’s rays ), up to 8 words/minute in Morse Code on a buzzer ( ie able to send and read/receive this code) and a certain amount of Cable laying. There was a general shortage of Wireless equipment and a bulky No.9 Set was sort of shown to us for a few hours. Some cross-country driving lessons (I suppose with the North African desert in mind) on 30cwt lorries, was imparted.

Commissioned in early June 1942 into the Corps of Indian Signals (I Sigs), what seemed strange at the time was, being asked where I would like to be posted. As a 2/Lt you hardly expect any choice being allowed nor was I aware as to the possibilities. Having been fed on Kipling’s tales of the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) of India’s tribal country, where over 70 per cent of the peacetime Army (British & Indian) operated or was located, I chose the NWFP. The upshot was that I was posted to Kohat District Signals.

After a train journey of around 36 hours I reached Kohat Railway Station. It seemed I was the sole passenger alighting there. While I was trying to figure out how to reach my new Unit, 2/Lt Bobby Gray (Royal Signals) turned up on a bicycle, accompanied by an AT cart (drawn by two mules) carrying a spare bicycle. He introduced himself saying that he had been deputed to fetch me, and had brought the cart for my baggage and a spare bicycle for me to ride back on to the Regiment.

On reaching the Unit I was taken to the Commanding Officer -Lt Col Hannah (Royal Signals)- who looked old enough to be on verge of retirement. He was kind and pleasant and welcomed me and explained to me the role of the Unit. In the course of the conversation he chanced to mention that I had an English name. To this day I do not know what came over me, I replied matter of fact like, “No Sir, some Englishmen must have an Indian name.” The CO not sure if he had been tactless, replied “yes of course, let us go to the mess, we shall have a drink together”. Being close by, we walked to the Royal Signals Officers Mess. Over a beer the CO and I talked about my college days in Lahore. We sort of became friends and at Dinner I was often seated next to him. Hannah was a gentleman and was ever at pains to put at ease the newly joined officers.

The following day at the morning parade, besides the CO and two Captains, among the officers there were sixteen 2/Lts including just three Indians – myself, BS Panwar and Bose. We were asked if we knew horse riding (my father used to arrange horse-riding practice for us during summer vacations) to which I replied that I could stick on to a horse, although I was not sure what horse riding in the Army implied. I was taken to the Unit Riding School –a sort of mud wall enclosure- and given a horse to ride. Apparently my equestrian performance was adjudged acceptable and I was given charge of over a hundred Horses and Mules. Mechanical transport there was none, except for two ancient chain and sprocket driven Crossley trucks that needed a fire extinguisher at the ready while being started, and one, long-nosed Chevrolet 15 cwt truck of recent design of USA make.

Being in charge of the Regimental Animals the morning PT parade did not apply to me. Instead I was to take them out daily, for exercise. While the men rode bare back, a mule or a horse, I as Officer-in-Charge rode a properly saddled charger (horse). All this was enjoyable and instructive. Among the other ranks (OR) there were some very fine horsemen and mule leaders, with long experience. They taught me all aspects of animal management covering training, health, feeding and fitness. I learnt a lot from the Regimental Veterinary officer and the Quartermaster. A mare named Peggy, I recall, was an excellent animal. With Bobby driving the Chevrolet along side of me I remember Peggy at full gallop could clock a speed of 41 MPH for nearly 3 minutes, with my eyes streaming in the wind, as I wore no goggles. Sadly one night this fine animal died suddenly, of colic according to the Vet.

Additionally, I was given the charge of a wholly British (R.Sigs) section of around 35 BORs for about 6 weeks, perhaps to ascertain how I took to them. Most of them were wireless operators by trade awaiting postings to Field Units. With equipment shortages there was not much signaling. However they were put through a lot of drill, animal management, route marches, kit inspection and the like. Apart from the Section Sergeant they were all conscripted for the war duration, from varying disciplines such as school-masters shopkeepers, farmers or artificers. Interacting with them was quite an experience. They were a simple lot with a sense of humor and overly fond of rum and beer. Some of them when short of cash, for buying more hootch, took recourse to pawning or selling their kit items. During one kit inspection three of them had not displayed their woolen jerseys while everyone else had. When asked I was told they were wearing them. On checking, two of them displayed a jersey sleeve each, worn under respective shirts, and the third was wearing the middle part. Somehow all this show aroused my suspicion and a further check revealed the three of them were sharing one jersey – the other two possibly pawned or sold theirs. The case was handed over to the Regimental Sergeant Major to go into.

Out of a total of 26 officers in the Royal Signals Officers Mess Kohat, Indians were a minority of three, as mentioned above. The rest were British. Naturally we had to get used to the English food and so on. Occasionally I tuned the mess radio to the A.I.R for Indian music. Once a British colleague ventured to remark that he did not like it -implying of course that it be turned off. To which I replied that, he was not expected to. Thereafter we remained at best of terms. He realized where a line must be drawn, to maintain healthy relationships.

Then there was the Warrant Officer Quartermaster named Clem South, who got a kick out of pulling the leg of any newly joined one-piper (2Lt). I remember him telling us quite seriously that for laying cable we should indent for sky-hooks to hang it from. On the whole he was a good jovial fellow, and helpful as well. Towards the end of the war I was to meet him again. By now he was a commissioned officer, a Captain Quartermaster in Seventh Indian Division Signals, while I was the Adjutant.

After a month or so with the Royal Signals Section, I was appointed OC 21 Mountain Artillery Regiment Signal Section, with its own set of chargers (horses) and mules. For Signals it was considered an independent command, rarely going to a 2/Lt. It was fun training with this Regiment of sixteen 3.7 inch howitzers – Four guns per battery, each with Two, 2-gun Sections, designated according to their class composition as Sugar (Sikh) & Mike (Punjabi Mussalman) Sections. It was a rewarding experience to watch the healthy rivalry-cum-competition between the Sugar and Mike Sections as also the gun-teams. Gunner officers were British, seconded from the RA (Royal Artillery), I being the only Indian officer among them. The men and the viceroy’s commissioned officers (VCO)- the JCO of today- were Sikhs and PM in equal proportion while my signalers were Dogras from the Punjab foothills. Teamwork in this regiment was excellent and British officers were able to get by with a smattering knowledge of Urdu, they were obliged to acquire on joining an Indian Unit.

Of course the entire Signal Section, like the Mountain Artillery Regt, operated on a Pack Basis ie on mules and horses, and they were very fine mounts indeed. An FS6 wireless set was carried on a mule as a side load balanced on the opposite side by the lead-acid battery of about the same weight. FS6 power pack was carried as the top load along with the base for a whip (rod) antenna. To enable a wireless operator to work the FS6 station on the move (walking beside the mule) 8 to 10 feet long leads connected his headphones and the (morse) telegraph key to the Set carried on the mule. The wireless operators were adept at sending and taking down messages while walking along side the mule, led by its mule leader, as a perfect team negotiating hilly terrain and narrow paths. The operator had to be careful indeed, to see that long leads of the headphones or the telegraph key, did not touch the rear quarters of the mule carrying the wireless set as it invariably sent the mule into fit of kicking.

Linemen (as also the Despatch Riders) of the Section were excellent horsemen, and could lay telephone cable riding at the gallop. They worked in pairs. One of them unreeled from one hand a third of a mile cable drum, while controlling his mount with the other hand. Second lineman followed him also at the gallop with a crook stick in one hand making the cable safe by pushing it off the track on to the trees and bushes clear of the track or road. Training with this Section was an exhilarating experience. Soon I too became a good horseman and played some Polo even.

Soon the Kohat troops including 21 Mountain Regt moved out on what was called a Column. We were the Kohcol and took part in the DATTA-KHEL Operation to teach a lesson to certain recalcitrant tribes in the interior of the tribal country – now-a-days referred to as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) in Pakistan, lying between its Western border and Afghanistan. It was a sort of mini-war lasting a little over three months. Troops marched the entire distance via Bannu Idak Damdil and Gardai where we had a few days respite, while others from Razmak side (Razcol) including 33 Indian Infantry Brigade, (later to form a part of the 7th Indian Infantry Division) joined us. It was at the Idak staging camp after Bannu, that I had my first ever taste of hostile fire or sniping. Some tribesmen under cover of darkness crept up close to the Camp perimeter and started to fire aimlessly into the camp creating much confusion with the bullets whizing overhead. The perimeter defenses of the camp returned the fire and soon the unseen snipers melted away. We discovered in the morning that the sole casualty was a mule shot through the ear. From then on sniping after dark while encamped for the night was a regular feature.

Datta-Khel operation itself lasted about ten days, but travel time with continual road opening effort took three weeks each way. Looking back it was more like a training exercise with troops. The enemy seldom presented a determined resistance. Old timers told me that an average tribal was a far cry from the warlike image he presented carrying a gun and a dagger. He fired only when he was certain of getting away, and, was allergic to being surrounded. He usually attacked small isolated parties more for loot and pillage, or when our troops had been careless. At the end of the days march, on reaching the chosen Camping site and unloading all the animals, it was usual for the junior most (myself) officer to take all animals for watering to some nearby stream with a skeleton escort. It was drilled into me that I must not be careless in posting sentries or lookouts during watering as that could invite disaster. I learnt also that the worst trait of Tribals variously known as Mahsuds, Wazirs, Afridis or Mohmands and so on, was un-reliability1. Recruitment from among these tribals, was confined therefore almost entirely for service in the Frontier Scouts, an irregular force located in their own tribal areas to police their own people. British attempts to enlist them as regular infantry had been unsuccessful, due mainly to their untrustworthiness and total lack of soldierly qualities, with a penchant for mutiny and desertion with arms.

Still for me being new to all this, there was ample excitement now and then, specially when a sniper’s bullet went whizzing overhead. My Signal Section had a couple of experienced NCOs, who had been on several such Columns, which helped. On the march we, that is the Kohcol, had to do our own ROD (Road Opening Day). It consisted of denying the tactical high points on both 4sides of the road we proceeded on, by sending up small parties of infantry to picket known Sangars –stone breastworks. As the Column advanced Pickets went ahead to secure the Sangars and were withdrawn as the rear of the Column, denoted by a large red flag, passed by.

A minimum of one Battery (4 guns) of Mountain Artillery Regt (some times two) was always in action ready to support, if needed, picket parties going up or withdrawing. It was a wonderful sight to watch a 3.7inch Gun carried on eight mules being unloaded, assembled and get off the first round in 40 seconds flat. Also a Battery in action had to leap frog at the double to be ready to go into action at the head of the Column. Regimental and Battery signalers accompanying the gunner OP officers were adept at conveying by visual signals, the fire orders to gun positions while moving up a hill. One man held the Lamp-Signaling aimed at the gun positions while the other tapped the fire orders on the key, and the former also read the incoming message.

On getting back to Kohat I was informed that I shall be posted to a Field Formation. Thus with just six months Service, my friend Bobby Gray and I were sent off to the Seventh Indian Infantry Division (the Golden Arrow) that was being trained in mountain warfare East of Peshawar in Shinkiari-Attock–Nowshera area. It was being prepared for active service either in extreme north west of India or in mountainous region of Northern Italy. It was still to receive 70 per cent of its equipment, which, for training purposes had to be imagined.

Bobby and I were lent the 15cwt Chevrolet truck to convey us to Nowshera – an 8-hour road journey. En-route while speculating what to expect in the new Field Formation, Bobby said that he had volunteered to come out to India to escape the nightly bombing blitz in his home country. By now we were passing a Field Regt RA and some British Other Ranks (BORs) were burnishing their newly received 25-pounder guns. Seeing the guns being readied Bobby became pensive and after a while informed me that he had been living with the premonition that he would not survive this war. How can you say that I replied, and gave no further thought. Sad to say, a year or so later in the Arakan (Burma) Bobby was killed when his slit trench took a direct hit from the Japanese shelling of his Brigade HQ.

We both duly reported to the 7 Indian Infantry Divisional Signals. I was allotted to 89 Ind Inf Bde Signal Section as its 2ic (Second in Command) while Bobby Gray went to 33 Ind Inf Bde Signals – also as the 2ic. My OC, Captain Kenneth Jones of the Royal Signals, was a strikingly competent officer, who had risen from the ranks after several years Regular Service as a Sergeant. He used to tell us how, in peacetime, he operated the Troopers (War Office London) wireless link to New Delhi Hong Kong & Melbourne. There was nothing that he did not know inside out, and, he soon became a sort of a role model for us. I actually envied him the way he could hold his own in most situations, as also set an a personal example for those around him. Whatever the circumstances he never spared himself. With an OC such as this one had to be on one’s toes all the time. It was hard work but I learnt a lot from him. In time he began to appreciate my efforts and, a more relaxed relationship, with a tinge of informality did creep into our interaction. But it had to be earned.

The Signal Section was from Saurashtra State Forces but was later replaced by an all Sikh section of Indian Signals, which had taken part in Operations against the HURs in the Thar Desert, working from camels under extremes of weather conditions and other privations. They were a fine body of troops, I was privileged to command in Burma fighting the Japanese.

PSG .

______________________________________________________________________________

Note1 It has been said, that in October 1947, it was Pakistan Military’s Blunder in choosing these very untrustworthy tribesmen as the cat’s paw, that they failed to reach Srinagar in time to be effective. When Maharaja Hari Singh of Jammu & Kashmir, acceded to India on 26 October 1947, the tribal raiders were already at Uri, mere 64 miles of a motorable road away, halted (unknown to us at the time) by a blown up bridge, and, by the tribals’ penchant for rape and pillage. That gave us time enough to fly out the 1st Battalion of the 11th SIKH Regiment, under the able leadership of their Commanding Officer Lt Col Ranjit Rai, who thwarted their advance at Baramulla. He was killed however, in this action, but saved the Valley no doubt.

7th Indian Division – Some Memories – Jungle Warfare

With less than six months service, joining (in Dec 1942) 89th Indian Infantry Brigade Signal Section, of the 7th Indian Infantry Division (7 Ind Div) was a bit puzzling at first. More I came to know this Field Formation, being readied for war, the more I realized that there was very little Indian about this Indian Infantry Division. My OC, Captain Jones, was British, and those days, an Indian Infantry Brigade Signal Section had ten BORs (British Other Ranks) under a Sergeant from the Royal Signals (R,Sigs), integral to its War Establishment (WE). Similarly Sapper Field Companies as also EME Workshops had on their establishment RE and REME components. Of the three Infantry Battalions in the Brigade, one was Indian – 7/2 PUNJAB mostly British officered. Of the remaining two, one was British Army – 2nd Battalion King’s Own Scottish Borderers (2 KOSB), and the other was 4/8th Gurkha Rifles. (Gurkha Units were the sole preserve of British Officers up till August 1947, i.e. Indian Officers were posted to Gurkha units after Independence).

At a rough guess Indian troops formed about 45 percent of the 7 Ind Div. Everywhere you met only British or British Commonwealth officers e.g. Australian Canadian Rhodesian or South African, even conscripted British Tea-planters from Assam or Rubber Plantations of Malaya and such like, in charge of Indian Troops. Proportion of BORs in 7 Divisional Signals as a whole was close to 45 per cent, and, its Indian officer strength seldom exceeded three – not counting the Viceroys Commissioned Officers or the VCOs, the equivalent of to-days JCOs.

My Brigade Commander, Brigadier C. J. Martin (Gharwal Regiment) was a long service Indian Army, from Britain. He was competent, devoted to the Service and to the Indian Soldier. With a slight wiry constitution, he looked a bit older than his age, but physically fit. Within a few days of my arrival he invited me (a Lieutenant now) to his home – he stayed close to the Nowshera Club with his wife and daughter. After drinks the four of us moved to the Club for dinner. It was a pleasant evening designed (I think) to get to know me. A reasonable rapport ensued, and thereafter, I found myself occasionally accompanying him as LO (Liaison Officer) to Divisional Conferences and such like – Brigade HQ still lacked its full complement of officers. This enabled me to know (and be known to) other heads of Arms and Services such as the Commander Royal Artillery (CRA)- Brigadier Hely. His four Artillery Regiments were all British – one of these was still without guns, having lost them at sea in a German torpedo attack, while en-route to India. Lt Col Cator was the CRE (Commander Royal Engineers). The medical set-up was under an Indian Officer – Colonel Burki of the I.M.S. (Indian Medical Service). In fact there was preponderance of Indian doctors in the Division, and an excellent job they did too.

Although I did not quite realize at the time, I find in hind sight, that, Signals is one Arm of the Service, in which even a Lieutenant with a few months service, begins his learning process by Inter-acting with a Brigadier an excellent initiation really, for acquiring fuller knowledge of warfare, and of other Arms and Services. Brigadier Martin was a great proponent of Battle Inoculation and, he designed several ways to accustom all ranks of the Brigade to face, unafraid, live bullets and artillery fire. I remember, once he had a Tripod mounted Medium Machine Gun (MMG) laid on a fixed line of fire. He then had a white tape placed on the ground parallel to the MMG fixed line, precisely 18 inches away. Every one was required to kneel down and put his nose on the tape with the MMG firing away live ammunition. Of course the Brigadier himself was the first to do so. Similarly there were regular sessions of advancing on foot in full battle order behind a creeping barrage of field artillery fire, and Martin urging us to get ever so closer to the exploding shells. Later when we encountered the Japanese in the Arakan (Burma), the actual hostile fire or the shelling we were subjected to, seemed a lot less frightening than the inoculation we had been through, while under training.

Company and unit training proceeded with great stress on night operations and night movement, including MT convoy driving at night without lights. There were critical shortages of equipment, but was being made up in dribs and drabs. We did have full complement of vehicles, mules and horses whose care took a lot of time. Wireless Sets were bulky and heavy, unsuitable for AT (Animal Transport), fit for CW mostly because of their low power output. Before very long we were to learn that the eventual destination of 7 Ind Div will be Burma to fight the Japanese. The entire Formation had to move to the Jungles of Central Provinces (CP) – MP now – around Chhindwara, for training in jungle warfare, in jungles made famous in Kipling’s Jungle Book.

Move to the CP began in late January 1943 – personnel and animals by rail, and vehicles by road. Detraining station was Narsinghpur, on the main line near Jubbulpore, and some eighty miles by road from Chhindwara. Once again back to section platoon company training with the difference that there was a definite objective before us – to master the jungle. Besides greater physical fitness, it called for ability to function under conditions of heavy rains and heat, as well as difficulties of movement. At times even Brigade HQ operated on man-pack basis. Also equipment deficiencies had been made up and, Battalion and Brigade exercises could be carried out with full complement of weaponry and ammunition. Recreation was limited to hockey and football or an occasional visit to Nagpur or its cantonment Kamptee. Attacks by wild animals of the jungle, disturbed by our presence, did occur, but no fatalities.

By March end all units returned to their respective camps, dumped surplus kit, and after a little rest were ferried by MT to their concentration areas for divisional manoeuvres, which were to prove of immense value. An outstanding lesson being perhaps the ease with which surprise could be achieved. Day patrolling, wide encirclement, unexpected encounters on jungle tracks helped to build in every ones mind a picture of what to expect in a war, in a forested hilly country with few roads or tracks. Often line communications were preferred to wireless which experienced static noise as well as screening particularly at night, among the dew laden forests. At times jungle paths were too narrow and slippery for a loaded mule to negotiate and alternative modes had to be evolved for carriage of equipment.

With about one year’s commissioned service, I personally was struck by the comradeship this integrated training engendered among the various units and sub-units of the Division. So much so that the troops at all levels came to recognize and know each other in a healthy competitive spirit. Equally Battalion, Brigade, (and even the Divisional) commanders, who never failed to set personal example in whatever was expected of the troops, became known throughout the entire Division. Teamwork was the watchword, and every one had a feeling of belonging, as well as a certain pride, in being a part of the Golden Arrow Division.

In time it became apparent that by the close of the monsoon (end August/mid September) our final destination would be the Arakan, to relieve 14th Indian Infantry Division. This Division had advanced to almost within sight of Akyab on the West Coast of Burma, when it encountered stubborn opposition along the general line Donbaik – Rathedaung. Additionally the Japanese launched an encircling counter-stroke forcing it to withdraw right back Northwards of the Maungdaw -Buthidaung Road. Chittagong was being bombed frequently, and there had been a couple of air raids towards Calcutta.

About this time I was sent off to the Tactical School (India) at Poona to attend a short (6 weeks) tactical course, which turned out to be a welcome change. The school was housed in Poona’s Deccan College with some really comfortable quarters. For weekly map reading practice we were taken often, to the jungle where the NDA has come up, or beyond the Khadakhwasla lake, in curtained off lorries and left there to find our way back to the School on foot, subsisting on havre-sack lunch. Most of the tactical training was in the shape of sand-model excercises By the time I completed this course my Brigade was on the move to Burma and I caught up with it at Dohazari.

For security considerations, components of 7 Ind Div were sent out by different routes to Chittagong – Cox’s Bazar area in lower Assam (now Bangladesh). 114 Brigade went by sea to Cittagong, via Deula (some 30 miles South of Calcutta) while my 89 Brigade was sent by road to Ranchi first. From there it entrained via Calcutta, Sirajganj (now in Bangladesh) on to the River Brahmputra and then by steamer to Chandpur, and again by rail to Dohazari Railhead – some 20 miles East of Chittagong. The rest of the Division embarked from Madras and Vizagapatnam. I marvel at the efficiency of the Movement Control (MC) organization of those days, considering that all movement East of Calcutta was mostly in hours of darkness under blackout conditions.

Indo-Burmese border was some 80 miles to the South of Dohazari Railhead, at a place called Bawli Bazar, where Burmese Arakan begins. Movement forward of the Railhead was by a narrow, strictly fair weather road and locally available barges plying on the coastal river Naf running parallel to this road. Troops and stores were ferried in barges, and the transport (both MT and AT) went down by road.

It is well to remember that Burma was a part of India (British Indian Empire) and was separated from India only in 1937, or two years before the outbreak of the Second Wold War. Several Indian engineers, doctors, as also Indian Army Units had served or worked in Burma prior to the exodus of 1942, occasioned by the Japanese invasion. Local population of Arakan, apart from the shy aborignes, the Kurmis, who seldom set foot outside the forests, there were Maghs – unmistakably Burman in type and pro Japanese; and Arakanese Mohammedans who hated both Japanese and Maghs. Amomg the ‘local inhabitants’ perhaps one should mention that very gallant band of Burmese officers who composed the ‘V’ Force. They lived (some of them had a price on their head) on the country among the Arakanese, collecting valuable intelligence, for which 7 Ind Div owed them much, specially in the initial stages.

About this time we received our new Divisional Commander, Major General Frank Messervy, (Indian Cavalry – 13th Lancers). His exploits in North Africa, in command of the Gazelle Force, comprised of 4th Indian Division and a British Armored Brigade and, story of his escape from the Germans, by his successful impersonation of an old soldier with a grievance, caught the imagination of the troops of his new command.

The Divisional task was to work its way beyond Bawli Bazar, astride the Mayu Range of hills, and the Kalapanzin valley to its East. In general terms Arakan may be described as a country of densely forested steep sided hills rising to 2000 feet, and paddy fields intersected by tidal creeks called ‘Chaungs’. Most of the forest is dense mixed jungle, impassable once one leaves the few tracks, without cutting one’s way through with a Dah, by now a standard personal issue to everyone. Paddy during the monsoon is thigh deep, and in winter, the banks or bunds between the small fields are high enough to hinder tank movement. I recall exercising Brigade Signals horses in dry weather by galloping across these bunds as in a hurdles race.

The Japanese held the line of Buthidaung – Maungdaw metalled road with its two tunnels through the Mayu hills, and the adjacent territory. Buithidaung was an important terminal for steamers operating from Akyab along the Kalapanzin River. By September 1943, we of the Seventh Indian Division held the line Wabiyn (89 Bde) to the West of he Mayu Range, and Taung (114 Bde) to the its East, a frontage of 12 miles. Some really aggressive patrolling towards the Japanese positions was activated to probe and dominate the no-man’s land. Divisional Tactical HQ was at Goppe Pass, at the Northern crest of the Mayu range, served by a particularly narrow and a difficult mule track. 33 Brigade was held in reserve.

In another two months 5th Indian Division was to assume responsibility for most of the Mayu and the low-lying country to its West, so that 7 Ind Div could accord its undivided attention East of the Mayu Range towards Buithidaung. Along with 26 Ind Div (in reserve) we became the XV Corps (HQ at Bawli Bazar), in General Slim’s Fourteenth Army. Brigadier Martin went down with tyfus so 89 Bde received a new Commander, Brigadier Allen Crowther of the Dogras. He was a real soldier’s soldier who quickly endeared himself to anyone he came in contact with. Also my OC, Captain Jones was moved to the Div HQ. His replacement, Captain John Wilson, an out and out civilian conscript, from a family of English ironmongers, was quite a change from Ken Jones. But, John was hard working, well meaning and always courteous. He quickly got down to learn and understand his all-Sikh signal section – his first time ever with Indian troops.

PSG ..

Dear Karan, There’s not much requiring annotation in this, except some terms & also things would be clearer if U had the relevant map with you. When you come over next time I shall explain things with help of the maps.

Pack stands for operating on foot without MT(mechanical transport), hence No vehicles, only Mules & Horses so we could operate cross-country. We carried all we needed say rations ammunition or other essential kit or fodder, on mules or camels even. AT Animal Transport –Mules & Horses

VCO – Viceroy Commission Officer – Present day JCO-Junior Commissioned Officer.

V-Force – Anglo-Burmans mostly operating clandestinely behind Japanese lines as they could easily mix with local populatin & speak the local language.

7th Indian Division – Some Memories – Arakan Box

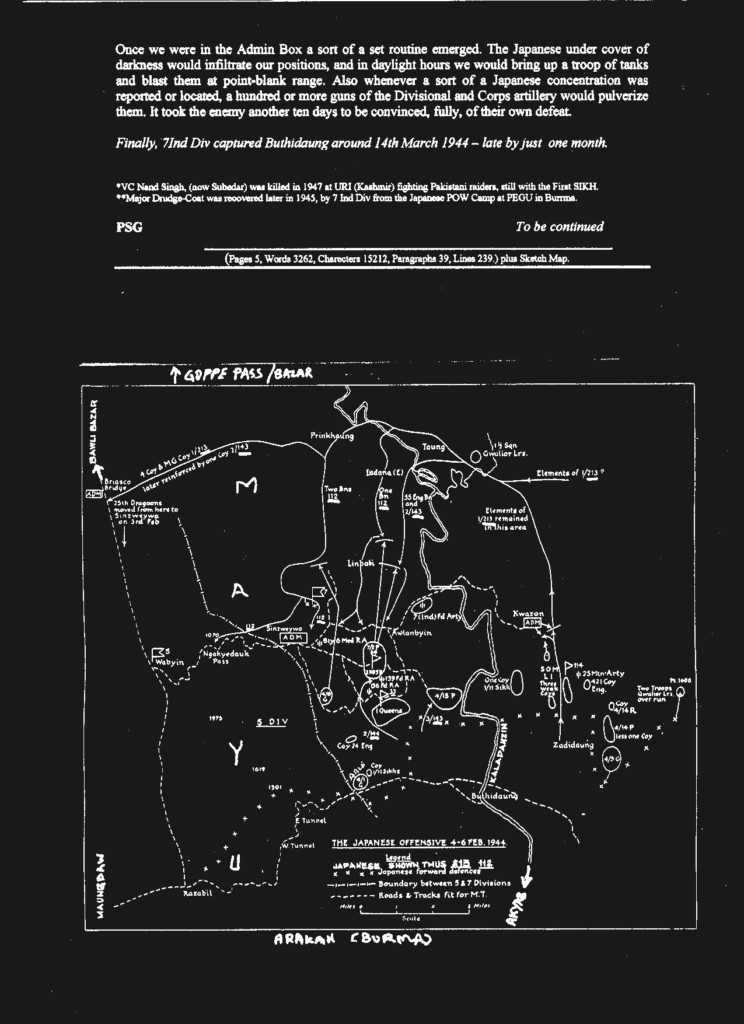

XV Corps plan was to capture Buthidaung – Maungdaw line, by mid-February 1944, with two Divisions, (the 7th and the 5th), and 26 Division in reserve. (See Sketch Map). Mine was 89 Brigade in 7 Div

Induction of 7 Ind Div into the Arakan, began in early October 1943, with two Brigades (114 and 89) up, and 33 Brigade in reserve. Div HQ was at Bawli Bazar. Patrol clashes towards Japanese positions were common and there were casualties on both sides. Line(telephone cable) laying parties operating in twos or threes had to be on the look out for signs of a likely ambush. 5 Ind Div was not expected for another month to assume charge of the Razibal Maungdaw side of the front. It was appreciated that for any meaningful action against the Japanese in Buthidaung, 7 Ind Div must have a road through the Mayu Range eastward into the Kalapanzin River valley, for moving heavier towed artillery, armor(Tanks), ammunition, engineer and other stores/supplies.

Problem- where to construct such a crossing – at Goppe Pass, or further south at the Ngakyedauk Pass. The former was nearest to Bawli but approach was knee deep in mud for the first 5 miles. Over this mud, bamboo mats had been laid which of course had sunk into the mud but still gave it some sort of a “bottom”. Along this personnel and loaded mules of 114 Brigade floundered till the foot of the pass. Here began the 1200-foot climb to the summit -a back breaking struggle up a path so steep that at places it was stepped and riveted with logs of wood. The surface was slippery and any breeze there was only penetrated fitfully through the dense steamy tropical. Falls and thrown loads were common which called for hand-carriage of loads. On the East side of this Pass, the track zigzagged down some 400 feet and then followed the boulder strewn bed of a mountain torrent. Here overhead trees met making by day, a greenish twilight till you reached Goppe Bazar, and thereafter by sampan on to Taung.

Fifteen miles to the South of Bawli Bazar, a little used track joining Wabyin and Sinzweya, called the Ngakyedauk Pass (often referred to as the the Okeydoke Pass) was chosen as the more suitable for building a road through. Hugh Bowen our Brigade Major (BM) took out a night patrol to confirm the possibility. I accompanied him besides two Engineers officers and a small protection party. It was a moonlit night and we had to be on man-pack basis. Moving through the eerie silence of thick jungle, broken only by our having to cut our way through the thick forest, or the cacophony of apes and such like, alarmed at our presence, progress was slow. Bright moonlight filtering through thick jungle wove strange patterns with its ghostly light, on the ground we trudged along. We returned the following night after a good look-see, and confirmed the feasibility of converting the track into a mule track first and a road thereafter.

Engineers target was a motor road over the Ngakyedauk Pass by December end. Employing a large local labour, under the supervision of the Commander Royal Engineers (CRE) – Lt Col Cator and his Field Coys, a mule track was ready in ten days in early November. It became a jeep track in another twenty days. By December end the road was fit for three-ton lorries, a truly remarkable feat of engineering, as the road was put through dense jungle, over a precipitous pass with a 1000-ft rise and fall in three miles, well within range of the enemy artillery. Thereafter bridges were strengthened further for the passage of medium tanks, (Grants) of the 25 Dragoons, who managed to join the 7 Ind Div on 3rd February 1944, barely 18 hours before Battle of the Boxes was to begin, while the Japanese (fortunately for us) remained oblivious of their arrival.

89 Bde Signals provided line-Telephone- communications to EngineerField Coys through some really difficult terrain subject to landslides and of course the blasting. It was extended to 7/2 Punjab in Sinzewya guarding the eastern end of the road. About this time we received comparatively modern radio equipment -WS 22 & WS 21- which could be carried man-pack or on mules more easily. Their performance on speech was superior as well. Only D3 single cable (earth return circuit) was used to save on weight, along with D-5 telephones. The mouthpiece (speech transmitter) of this telephone was of the carbon particle kind, which was rendered fairly ineffective when wet, due to rain or the nightly condensation of dew. Dispatch riders (DRs) performed on ponies as well as motorcycles, and on foot even. Replenishment mostly was along the Naf River in local barges.

To ease matters a system of composite rations based on shakarpara biscuits and tinned stuff had been introduced. Four man rations were packed into a sealed ghee tin. Unfortunately the ration cigarettes were included also. Although no open complaints reached me, there was visible consternation among my Sikh Signal Section when these cigarettes spilled out of these tins. On learning the cause of the unhappiness I addressed the entire Section and assured them that henceforward their rations will not contain cigarettes and for the present they should just throw away the cigarettes. On noticing that my assurance had had the desired effect, I added politely that I would not be able to ensure that the train or the sampans bringing the rations would not be carrying cigarettes. I think the men saw the point of it. But, I must say the Supply base took really swift action in delivering subsequent packaged rations without cigarettes.

Christmas of 1943 saw the induction eastward of the Mayu, Field as well as Medium Artillery – close to a hundred artillery pieces, including 7 Indian Field Regt. Earliest to arrive via the Goppe Pass, was 25 Mountain Regt. My batch mate, and a friend from my college days in Lahore (now in Pakistan) Lt Hari Singh was its Signals Officer and this Regt was in support of the 114 Bde East of the Kalpanzin River.

Sinzweya at the east-end of the road was a largish clearance surrounded by low hills. It quickly became the Division’s administrative area (later to become the famous Admin Box) comprised of ammunition and supply dumps, engineer stores, an MDS (Main Dressing Station), Service Corps transport companies (MT & AT), workshops and such like. Once 5 Ind Div took charge of the Maungdauw front, 89 Bde moved to the East of Mayu Range and quickly got down to the business of pressuring the enemy. KOSB (Kings Own Scottish Borderers) occupied the feature called Able close to the Buithidaung end of the metalled road from Maungdaw. 33 Bde was on our left and 114 Bde was to its further left across the Kalapanzin, stretched in a line, rather dangerously – 7 Div was without any depth. Div HQ was first at Badana, having negotiated the Goppe Pass along with 33 Bde. It later established itself as a full-fledged headquarter about two miles to the north east of Sinzewa Admin area.

A worrisome situation arose when the Japs occupied three small features (Three Pimples) North of Able and succeeded in isolating the KOSB. Lt Stuart was its Signal Platoon in charge and a friend. A few days earlier he and I together had reconnoitered this area and, between us had a good idea of various paths and Tracks. I had visited Stuart and my Signal Detachment under Naik Amar Singh, barely 36 hours before this Battalion was cut-off, and, had ridden back along the Pimples. 89 Brigade HQ was about a mile from Able although travel distance was circuitous hence longer.

Soon KOSB was running short of rations, ammunition and petrol for charging batteries for the wireless set. Wireless as communication means was insecure and unreliable. On 20 January some ammunition was delivered in tracked carriers under Japanese mortar fire, which also destroyed the telephone line. Attempts to restore the line employing a tracked carrier were only partially successful. Stuart and I decided to lay a line from both ends, under cover of darkness, to an RV under the ledge of the Pimple nearest to him. On the night of 22nd I set out with Naik Inder Singh and Sigm Gurnam Singh to lay a fresh line past (and close to) the Pimples keeping clear of carrier routes. Stuart duly met me around midnight as agreed, and the line was put through. While approaching the Pimples RV, enemy interference was limited to firing of a few flares as they heard crunch of our footsteps on the dried up paddy. After each flare we three had to lie still among the paddy for good 10 minutes so as not to arouse more curiosity. Strangely this line, under the very nose of the enemy, held without further damage despite artillery and air bombardment. This telephone line became a vital link in planning of the subsequent operations. For several days dive-bombers of the Air Force pounded the Japanese, each time leaving behind some unexploded 1000 pound bombs timed to go-off at varying intervals during the night, thus keeping the Japs awake. Eventually a surprise night attack by 7/2 Punjab brought relief to KOSB. For this night unexploded bombs left behind by the Air Force were without fuses.

On 2nd February 1944, 9th Indian Infantry Brigade under Brigadier G.C. Evans, from 5 Ind Div, became responsible for our area. The following day 89 Brigade, less 4/8 GR, went into reserve along with the KOSB and 7/2 Punjab, in an area behind 33 Brigade. At dinner on the evening of 3rd February, I remember telling Hugh, our BM, (Brigade Major Hugh Bowen of the Suffolk Regt) that I did not relish the idea of being a Reserve Brigade, because it meant that, we could be pushed into any sticky situation at short notice. While agreeing with me he said, we had been in action continuously for over four months some rest had to come our way. Next morning, 4 Feb, around 9 A.M as I was trying to listen to BBC news, I could hear the BM shouting into his dew laden telephone to the 7 Div GSO-1 “did you say Japanese were in Taung and we have to move out immediately to deal with them.” I was astounded, to say the least, at my fears of previous night coming true. 89th Brigade was required to find, fix, and destroy the enemy column. Within an hour the Bde moved north with two battalions up, 7/2 Punjab right, directed on Badana East and, 4/8 Gurkhas left, directed on Badana West. (See sketch map). KOSB and Bde HQ followed the 7/2 Punjab. 139 (Jungle) Field Regt RA provided close artillery support. Fitfully, while on the move, our Column was harassed by enemy artillery from hill features to the east of the river Kalapanzin. We walked past the sprawling 7 Ind Div Headquarters, looking very functional and peaceful, oblivious of what was in store for us in the coming days. Nearby we created a Brigade dump for our non-essential equipment and baggage.

First contact was made that evening by 7/2 Punjabis and Japs appeared to be taken by surprise, and hesitated, affording us a little breathing space, on this so far somewhat breathless day. By nightfall KOSB and Bde HQ were firmed up east of Linbabi and 7/2 Punjab settled them-selves on a small hill to our right. Very early morning of 5 February Japs recovered from their shock, and hurled attack after attack on both positions. By midday the enemy succeeded in isolating the Brigade Headquarters. Sigm Sardara Singh sitting in a trench next to me was wounded in the shoulder while we were trying to raise Divisional control station; 89 Bde Headquarters was under attack.

A company of the 1/11 Sikhs, commanded by Major ‘Bimboo’ Spink (second generation Sikh Regt officer ex UK) was the 89 Bde HQ Defense & Employment Coy, an appellation (and role) the officers and the men of this renowned Battalion –the First Sikh- viewed with distaste. Bimboo and I were real good friends (due partly to both being in charge of Sikh troops) and also, I was struck by the way he cared for his men who loved and respected him in equal measure. Spink, always on the look out for a fuller operational role, proposed to the Brigade Commander –Allen Crowther- that before nightfall, he must get rid of the Japanese posing a threat to the Bde HQ. The Brigadier agreed, and despite protestations of his Coy Subedar, Jagir Singh who himself wanted to carry out the assault, Spink led the attack and succeeded in dispersing the Japs in a purely Infantry Battle. But, to his dismay, almost towards the end he received a bullet through the right eye. After a quick patch up at the A.D.S he was evacuated the same night, hand-carried and escorted by his own men. Despite being attacked en route the Party returned by first light after leaving Spink at the M.D.S. who were able to send him further on, by MT. A few months later he was back –this time as the (one eyed) Battalion Commander. His greatest regret (he told me on return) was that he had to be away (sick) when the First Sikhs in March 1944, took part as a Battalion, in the battle for Buthidaung, and, their Naik Nand Singh earned the Victoria Cross1.

On our left, 4/8 GR with a troop of tanks from 25 Dragoons in support, made contact with a large Japanese force which appeared to be heading towards the 7th Division Headquarters, at a point some 2 miles to its north. Next morning (5 Feb) a full-fledged battle raged to the west of us in the lower reaches of the Mayu range. While this was going on the rear column of 4/8 GR came under heavy MG fire from an area through which its A Coy had passed a short while before. Immediate counter attack supported by tanks restored the situation somewhat but the forward two Coys came under more heavy attacks and lost touch with Bn HQ. While the Gurkhas took up a position for the night, despite some patrolling, the situation remained confused. Heavy static interference rendered wireless communications with 89 Bde ineffective, and no orders or reports could be passed. Tanks were withdrawn to the Admin area, before last light, for replenishment.

On 6th Feb morning, Divisional HQ was attacked in strength. Signal and the ‘G’ areas, were the first to be over run. Signals, along with several men, lost Captains Bichard & O’Donoghue (on duty) as killed, and Ken Jones was severely wounded resulting in the loss of a leg. Second in Command of 7 Ind Div Signals Major Drudge-Coats2 was taken POW. Codes & Ciphers fell into enemy hands and were compromised.

Wireless and line communications to/from the Divisional HQ went dead. It seemed to the three Brigade Commanders, (still in radio contact with each other), that Divisional Headquarters was a ‘write off’. They decided to stay put in their respective areas and withdrew their exposed sub units into tightly held defended localities or Boxes – 33 Bde was to be the coordinator till more was known. In many ways it was a really dark day, and the fog of war had descended so thickly over the entire Seventh Indian Division that no one knew what was going on even round the corner, let alone on “the other side of the hill”.

About 11 a.m a message arrived via the artillery radio link that 89 Bde less 4/8GR should fall back to the area of 7 Ind Field Regt close to Awlynbin and protect the gun areas. Move back commenced that night, after dark. En route a tidal chaung had to be crossed. Troops with the little Equipment they carried crossed over around midnight in locally available boats or sampans. I was left this side of the Chaung in charge of about 200 mules and a platoon of 1st Sikh for protection, with instructions to cross over when the tide went down –expected to do so around 7 a.m (7 Feb). As we waited shouts of ‘Banzai’ –Japanese war cry- could be heard from nearby hills. At daybreak the water level still appeared to be high. With help from our ‘V’ Force interpreter the village headman was located who showed me the spot where the animals could wade through. I rejoined my Bde by 9 a.m. and the animals reported to respective units. As I crossed over a pleasant surprise greeted us – Brigadier Crowther was waiting to welcome us, typically, more to see for himself if we needed any help.

It was the fourth day without replenishment. We were running short of rations and ammunition. While the local defense was being organized we heard heavy firing coming from an oblong hill to our left where 7/2Punjab was to establish a defended locality. It lasted about an hour, and 64 injured men and officers of 7/2 Punjab including Lt Col Rouse the CO, turned up at 89 Bde HQ bandaged or in slings. Apparently the Bn HQ was attacked before it was quite dug in. Brigade Signals wireless detachment with the Battalion, under Naik Sadhu Singh was missing. (Three days later he with a few others turned up at the Bde HQ after successfully dodging the Japanese, looking tired, starving and emaciated, but in good heart).

The same afternoon (7 Feb), 3 tanks of 25 Dragoons brought us some rations and more importantly NEWS, as to what had happened to the Divisional Headquarters. We learnt that the Divisional Commander Major General Frank Messervy and most of his staff including the CRA Brig Hely and C Signals Lt Col PMP Hobson (R.Sigs) had escaped into the Admin Box. Apart from the clothes they stood in, and their personal weapons they had lost everything. And, that they were busy regaining control. Also arrangements for airdrop of supplies and ammunition were under way. Wireless communication with Div HQ was ‘through’ that evening with the help of a wireless set borrowed from a tank of 25 Dragoons. Brigadier Evans’ 9 Brigade, was also manning a substantial part of the Admin Box.

To save on batteries and charging, all four stations were to come on air thrice a day to exchange information. Brigades were the three Charlies – Charlie One(33 Bde) Charlie Two(89 Bde) & Charlie Three(114 Bde). While enemy moves or actions could of course be spoken off in the clear, anything concerning our moves or plans had to be cloaked in parables or by reference to events that could not be known to the enemy. By virtue of long training together as a division and working with each other, most officers were able to recall some common experience to illustrate what was being conveyed. After a couple of days 5 Div(Charlie Four) and 15 Corps(Charlie Five) started to come up on our frequency, mostly to listen in. One day I was operating Charlie Two, when Charlie Four butted in to say he thought Charlie Two had a JIF (Japanese Inspired Forces i.e.INA) operating it. General Messervy who never forgot a name or a face replied “Oh, I know him, he is Allen’s Sparks” – meaning Brig Allen Crowther’s Signals Officer.

First airdrop was attempted on 8th February but, had to be aborted, as the Japanese fighters appeared simultaneously – one Dakota aircraft was lost. However the Dakotas returned at night and completed the drop using light flares – ‘pills’ (ammunition) only, which of course was the right decision by RAMO. Rations and other goodies came on subsequent nightly airdrops. Thereafter it was only a matter of time. Japanese had banked on 7 Ind Div’s pulling out by day six (9 Feb). This did not happen. The Japanese had brought ten days supplies, and had planned to live off our stocks thereafter. None of us, at any level, ever thought of pulling out, and the Japanese defeat was complete by 25 February. It was, to my mind, the result of the spirit of goodwill, friendship, and above all, confidence in one another achieved during training as a Division, which never failed in action, and grew steadily in spite of setbacks.

Maximum number of attacks fell upon the Admin Box. 4/8 GR, who having known well the foothills area had managed to reach it in small parties. Along with 24 LAA Regt (RA) and elements of various Administrative Units, 4/8 GR bore the brunt of these attacks. As Japanese pressure increased, KOSB and 89 Bde HQ (less 7/2 Punjab) were also brought in on 15 February 1944 by way of enforcement. It was a night move and on the way our column was attacked by largish Japanese fighting Patrol. This caused considerable confusion and some casualties, including two Signals. In this melee 89 Brigade Signals took one Japanese POW, a gunner apparently. Dutifully, he was carrying the gun sights of his gun. He behaved as if he was scared of being abandoned by us – surrender in the Japanese eyes was looked upon as an extreme loss of face for the whole Regiment and merited harshest punishment-Harakiri even.

Once we were in the Admin Box a sort of a set routine emerged. The Japanese under cover of darkness would infiltrate our positions, and in daylight hours we would bring up a troop of tanks and blast them at point-blank range. Also, whenever a sort of a Japanese concentration was reported or located, a hundred or more guns of the Divisional and Corps artillery would pulverize them. It took the enemy another ten days to be convinced, fully, of their own defeat.

Finally, 7Ind Div captured Buthidaung around 14th March 1944 – late by just one month. PSG ______________________________________________________________________________

1VC Nand Singh, (now Subedar) was killed in 1947 at URI (Kashmir) fighting Pakistani raiders, still with the First SIKH.

2Major Drudge-Coat, later in 1945, was released from an abandoned Japanese POW Camp at PEGU in Burma, by the Seventh Indian Division

7th Indian Division – Some Memories – Arakan – II

Part 3 described how my fears of being a reserve formation, came true within the twenty-four hours of assuming such a role. 89 Brigade had to move out, on an all-pack basis (ie on Foot with Mules/Horses), at one hours notice on 4th February 1944, to confront a largish Japanese force some six miles to the rear of our Divisional Headquarters, and what all transpired in the ensuing ten days.

By now (15 February) ours was a weak Brigade. 4/8 Gurkhas had been separated from us when the Divisional Headquarters was over run on Sixth February. It managed however to reach the Admin Box in dribs and drabs to form a weak Battalion by 8th February or so. It was allotted the task of holding the east face of the Box. 7/2 Punjab, and our British Battalion –Kings Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB) had received a fair amount of mauling and were carrying a number of wounded, since evacuation was no longer possible. Brigade Headquarters defense Coy of 1 Sikh had been similarly depleted – their commander Major Spink, had been wounded and evacuated, its command having passed to their Subedar Jagir Singh.

In the care of the wounded, no amount of praise is enough for the hard-worked medical staff of our Advance Dressing Station (ADS) and the self-less devotion of its doctors led by Captain Banik of the IAMS(Indian Army Medical Service) –AMC(Army Medical Corps)of today. Evacuation of seriously wounded was possible only after 10th February. For this, single engine L5 light aircraft were used, operating at great risk, from the supply Dropping Zones(DZs), in daylight hours. L5 pilots were mostly American who described themselves as the conscientious objectors, meaning they would soldier (and risk their lives) as lifesavers, but not as killers. An L5 aircraft could carry only one casualty per sortie – the amount of hazardous flying undertaken by these brave flyers can be imagined. Many a stretcher cases were conveyed to makeshift L5 landing strip on the shoulders of their comrades, also at great risk at times over difficult soggy terrain.

Living in the jungle was hard, aggravated by leeches, mosquitoes, ticks and the attendant fevers. Fungus saturated wet soil produced athletes foot and other annoying skin conditions. It was winter and nights were cold, accompanied by heavy dew or even rain at times. Rain capes were the main protection supplemented to an extent by the parachutes that fell from the sky in the nightly supply airdrops. All cooking and dining had to be completed before nightfall and total blackout observed thereafter. One hundred percent stand-to (night-duty) was a common feature of life. There was neither the opportunity nor the wherewithal for a bath. If lucky an occasional wash all one could hope for. I had no bath for all of 23 days that we remained surrounded by the Japanese.

Seventh Indian Division had no rearward communications – signal or otherwise. So our replenishment needs could not be conveyed. Yet the Rear Air Maintenance Organization -RAMO at Comilla or Calcutta displayed amazing competence, who on their own figured out what all ought to be air dropped when and where. For example the initial airdrops delivered only ammunition, which was indeed more important – one could last without food but not ammunition The joke was that supply by air (without Indents) was lot more effective in terms of promptness and quality as compared to the usual land based system.

Reverting to 15 Feb 1944, the British Battalion (KOSB), HQ 89 Brigade, my Signal Section and other ancillaries moved out around 11 P.M to join (reinforce) the Admin Box. One Coy each, from 7/2 Punjab and 1 Sikh, stayed behind to protect the guns at Awlynbyn a little to the rear of 33 Brigade. Aim was to reach the eastern entrance (held by 4/8 GR) before 2 AM when full moon was expected to appear. The journey was through low-lying forested hills interspersed by dried up paddy fields surrounded by two-foot bunds. As the Column neared the east entrance we met a Japanese Patrol of about 60 men and a minor firefight ensued, which caused the mules to stampede and, much confusion besides. It is unclear who was surprised more, the enemy or ourselves. People ran helter-skelter to control the mules and retrieve dropped loads. In the process most of us lost all sense of direction in the darkness, in fact lost our way. A curious thing happened before my own eyes while I was crouching behind a paddy bund. Not far from me, a KOSB man approached gingerly in the dark another man thinking him to be from his own side. As soon he was near enough and found him to be Japanese, the both of them dropped their respective packs and scooted in opposite directions. Of course assisted by my orderly Kartar Singh, I retrieved both the packs,

Two of my men, Naik Sarwan Singh, an excellent wireless (morse) operator, and one other (whose name escapes me), in the general confusion, attempted to return to from where we had started. Unfortunately, as they approached own positions, they were shot dead, mistakenly, by own troops who did not expect anyone to be there. It took nearly two hours to collect as many of our people as possible, and, a depleted lot made it to the eastern entrance, (by now) in full moonlight. A third of my Brigade Signals including the Section VCO (JCO of today) Jaswant Singh, along with some of the KOSB missed the entrance but managed to reach a hill feature a little to its South. At daybreak the VCO came up on the air to inform us what had happened. They all came into the Admin Box the following night.

Commander Signals 7th Indian Division, Lt Col PMP Hobson, (Royal Signals), welcomed my Brigade Signals. He also borrowed some equipment since he had lost all of his,-besides seven British officers, eight British and ninety Indian ranks killed or missing, in the fighting that took place on the morning of sixth February. We learnt that after destroying the Div HQ, the Japanese attacked the Main Dressing Station (MDS) located in the Admin Box area, where they shot or bayoneted our wounded and took away medical staff as prisoners. Jap shelling was able to set fire to ammunition dumps located in the Admin Box which was so packed full of men, material and animals that smallest bombardment could easily result in considerable loss/damage. By Eighth February Japs had cut off the Wabyin-Ngykadauk road, effectively isolating the entire 7th Indian Division and denying it the land route.

Also, from 10 Feb onwards there was attack after attack for three days. Many of these succeeded in reaching vital hill features overlooking the Admin Box and each time they were repulsed by artillery bombardment followed by infantry supported by Tanks of 25 Dragoons. The debt owed to these tanks and their crews cannot be over-emphasized. It was their accurate, high velocity, close range blasting which was the deciding factor in putting our infantry back whenever the Japanese penetrated our defenses or captured any vital positions. Consequently most hill features in and around the perimeter looked bare, stripped of their undergrowth, leaving behind leafless tree stumps.

Similar attacks occurred also on 33 and 114 Brigade positions. During one such attack Major MG Bewoor (elder brother of the later day Army Chief, General GG Bewoor), of Madras Sappers, commanding 421 Field Coy attached to 114 Brigade, was killed. Apart from the doctors, he was the highest ranked Indian officer in the entire Seventh Division at the time, and the only Indian holding Major’s rank.

From 16 Feb on, 89 Brigade took charge of defense of the Admin Box. Brigade Signals quickly laid down a network of telephone cables to the various defended localities, in such a way as to afford two or more routings to each position. Most of this work was completed along forested narrow slippery tracks. All available hands including the mule leaders were pressed into completing the line-laying task. Linemen and dispatch riders performed mostly on foot, and often under hostile fire.

While Seventh Indian Division stood its ground regardless of several setbacks and casualties, subsisting on air-supply, XV Corps (unknown to us) had ordered the reserve Division – the Twenty Sixth- to our rescue. Negotiating the difficult Goppe Pass it proceeded to mop up Japanese well to the north of the Admin Box( ie behind us ) Accidentally while scanning the air waves, we picked up occasional coded signals of what seemed to be its advance elements, leading to the conclusion that a fresh pressure was being applied to the enemy from the North, which was heartening. We of course lacked the means to decode these tit-bits of information.

Fifteen Corps Commander General Christison had ordered GOC 5 Div, General Briggs (code-named the ‘umbrella man’ on the air, after the English umbrella makers of that name) to clear the Japanese from the Nyakydauk Pass and restore the road communication between the Seventh and Fifth Divisions. Fifth Division was already stretched and its efforts were less than successful, with the meager resources it could spare. I learnt that on 14 Feb they did succeed briefly to open this Pass and 5 Div Signals even put through a telephone line but it lasted only a few hours as the Japanese reoccupied this pass.

The Sixteenth February was a red-letter day for the defenders of the Admin Box. Not only had the garrison been reinforced, but also on that day a patrol of 25 Dragoons made contact with the forward elements of 26 Division near the old (abandoned) Divisional Headquarters –To our North. Despite the obvious loss of initiative the enemy had not quite given up hope yet, and continued to hurl suicidal assaults against our positions, accepting ever mounting casualties. The enemy suffered their heaviest losses on 21st and 22nd February both at the eastern and western perimeters of the Admin Box. Around midday on 23rd February the KOSB made contact with the 2/1st Punjabis and 4/7th Rajputs of the 5th Indian Division, and twenty-four hours later the Pass was open to traffic. Tragically, almost the last burst of fire mortally wounded Lt Colonel Maclaren commanding the KOSB, their second CO to fall in a month.

The first priority was to get away the wounded – nearly 500 of them. Nothing was allowed over the pass until all casualties had been evacuated. On the same day (24 February) General Messervy issued an operation instruction to put in motion the Seventh

Division’s original offensive towards Buthidaung, forestalled and delayed, due to Japanese encirclement. On 25 February and on succeeding days, many fleeing Japanese parties were intercepted and dispersed or destroyed. The largest party was seen entering a ravine and was subjected to a heavy artillery bombardment. A follow up patrol found over 300 dead bodies of the Japanese. Among them was recovered bits and pieces of General Messervy’s personal kit abandoned on 6 Feb when his headquarters was over run, including his ‘Brass Hat’ which was retaken into use immediately and (I suppose) worn for the rest of the war.

By the first week of March preparations for assault on Buthidaung were well advanced. Over a hundred artillery guns to support the operation were assembled, comprising Seventy two 25-pounders, Sixteen 3.7-inch howitzers, and thirty-two 5.5-inch mediums. Much to the satisfaction of its rank and file, 1/11 SIKH were to participate as a whole battalion, first briefly under 33 Brigade and then revert to 89 Brigade as it passed through for the final push to capture Buthidaung.

The battle commenced on 6th March around 10 P.M with the roar of over 100 guns opening up together – a roar naturally intensified by the myriad echoes from the Mayu hills. Even the bright moonlight was eclipsed for a while by the brilliance of the gun flashes. For me, it was another first experience of such power. As the concentration lifted the leading companies of 1 Sikh and 4/15 Punjab assaulted with great dash and carried all opposition before them with negligible loss. By first light on 7th March outlying positions to the west of the objective were consolidated. Sydney Lyons the Brigade IO was down with fever. I accompanied my Brigade Commander, Allen Crowther doubling-up as Signal cum Intelligence Officer and was lucky to be able to observe the battle from a forward vantage point. The Japanese did deliver a couple of ineffective counter attacks but own positions held.

Next, a really fierce battle for the capture of Buithidaung occurred on 11 and 12 March. By now 1/11 SIKH having reverted to 89 Brigade took the place of 7/2 Punjbis, who had suffered heavily the previous day in the battle for Hambone feature including loss of their CO – Lt Col Rouse. First Sikhs were in the lead and 4/8 Gurkhas were to pass through. Various sub units were too close to the enemy, and to each other, precluding the use of artillery bombardment. It was an Infantry battle with limited tank support. It was here that Naik Nand Singh of 1/11 SIKH earned the Victoria Cross, when despite being wounded he led his Section(about 8 men) to clear three Japanese machine gun nests one after the other. In another two days the Japanese were sent careering southward, and capture of Buithidaung (and the first time ever Japanese defeat) was complete. 26 Indian Infantry Division relieved the Seventh, and by 20 March, 89 brigade was concentrated in Taung area, hopefully, for some rest and refit. But that was not to be – the Brigade was on the move again to join the hard pressed garrison in the Imphal plain.

PSG ….

“ The Battle of Arakan was the First occasion in this war in which a British and Indian Force

has withstood the full weight of a major Japanese offensive –held it, broken it, smashed it into little pieces and pursued it. Anybody who was in the 7th and 5th Indian Divisions and was there has something of which he can be proud indeed.” – so said General Slim, Commander of the Fourteenth Army.

read your fathers memoirs – very vivid and helped to fill in something of what my grandfather experienced during the war – Second in Command of 7 Ind Div Signals Major Drudge-Coates

I’m glad someone else with a connection to 7 Ind Div Signals found this. Those were interesting times and they are much more vivid when one has a personal connection. If there are other memoirs of 7 Ind Div, I’d love to read them.

This was one of the most informative pieces I have read on 89 Brigade of 7th (Indian) Division of which my own regiment (KOSB) was part. Of particular interest to me as my late father served with 2KOSB pre-war and during the Burma campaign. Thank you so much.

Really glad to hear that! I hoped that putting this up would find others looking for such information. I wish I’d asked my grandfather more questions but I was too young to realize the full significance of these events. I’d be happy to read any other accounts.

Greetings from Canada,

My dad was an officer with the 25th Indian Mountain Artillery Regiment.

He stayed with the military until ‘47 when he went back to the UK. Eventually moving to Canada.

Can anyone tell me why the last four folios of his military records would be embargoed until 2044 and 2045?

Regards, JHMartin

Hello John,

It’s fascinating to hear from people who had family in the Burma campaign. I’m afraid I don’t know why the military records are embargoed. The Burma Star association could be a point of contact: https://www.burmastar.org.uk/ .

Karan.

Thank you, Karan

I’ve tried Burma star Canada and UK. No reply.

According to the British Library, the last four folios should be available to me in 2021.

I’ve written to contacts at the BL, and to researchingww2.co.uk, who provided me with my fathers military records and available war diaries.

As soon as I asked this question, correspondence was cut off.

Curiouser and curiouser.

However no one seems to want to answer the question and I hope, but don’t think, I’ll be around until 2044.

Any more advice?

Cheers

Thanking you, in advance,

JHMartin

Many thanks for this, my Uncle Harry served with 2KOSB and I look forward to re-reading his unit’s war diary in conjunction with your grandfather’s account. Harry was promoted to Lance Corporal (war substantive) during this period.

2KOSB was later flown in to reinforce Imphal and following the action at Kanglatongbi Ridge, marched across rough country in monsoon conditions to the hill village Japanese stronghold of Ukhrul. Harry (now ws Corporal) was wounded by sniper fire in the assault and died within 24 hours. He was 21 years and 3 weeks old.

Lest we forget.

It’s tragic to hear about your Uncle Harry’s sacrifice when he was so young. Indeed, the Burma campaign is less known than other WWII campaigns, but was an unrelenting war fought in jungle terrain. I hope we don’t forget these events, and I’m glad we can share these experiences. I would be very curious to know if 2KOSB’s war diary overlaps with the events mentioned. It seems that Harry’s actions follow immediately after the events related here.

Thanks for sharing this. My grandfather was in the 7/2 punjab and this fills in a lot of gaps.

Nice to hear that :) If you heard any stories, I’m curious to hear them (and probably other readers here are curious too). It’s amazing these stories happened not that long ago.